A topological analysis of the Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model

A detailed analysis of the bulk topology in this well-studied model.

Introduction

While this represents nothing particularly new about this well-studied model, I have found most references on this subject gloss over or miss certain points that I think are important for getting the full picture of this model and what it can teach us regarding topology in condensed matter systems. The Su-Schrieffer-Heeger model, or SSH model for short, is in a sense one of the simplest models of topology and the resulting edge states (the bulk-boundary correspondence), so a full analysis of it helps to shed light on other models in higher dimension with topologies that might be a little harder to imagine. The model is a simple tight-binding model representing polyacetelyne C2H2 but it also has an artificial particle-hole symmetry which when interpretted as a model of Bogoliubov-de-Gennes quasiparticles (in a $p+ip$ superconductor) it becomes an exact symmetry.

Model definition

The molecular chain is a combination of weak bonds and strong bonds and thus has two (low energy) configurations that are degenerate:

The tight-binding model for the SSH model takes the form

\[\begin{equation} H = - \sum_{n} \left( t_1 \lvert n, A \rangle\langle n, B \rvert + t_2 \lvert n+1, A \rangle\langle n, B \rvert + \mathrm{h.c.} \right), \end{equation}\]where $n$ labels the unit cell $A$ and $B$ are the different sublattices with hoppings $t_1$ and $t_2$ between them. We can introduce Pauli matrices via the sublattice space $ \lvert A \rangle \langle B \rvert = \sigma^+ = \sigma_x + i \sigma_y$ (and $\sigma^- = (\sigma^+)^\dagger$), giving the Hamiltonian the form

\[\begin{equation} H = - \sum_{n} \left( t_1 \lvert n \rangle\langle n \rvert \otimes \sigma_x + t_2 \lvert n+1 \rangle\langle n \rvert \otimes \sigma^+ + \mathrm{h.c.} \right), \end{equation}\]to diagonalize the model we note that $\lvert{n+1}\rangle = e^{-i \hat k} \lvert{n} \rangle$ where $e^{-i\hat k}$ is the translation operator by a unit cell. Using completeness $\sum_n \lvert n \rangle \langle n \rvert = 1$ we can write down our Hamiltonian as

\[\begin{equation} H = - (t_1 \sigma_x + t_2 e^{-i \hat k} \sigma^+ + t_2 e^{+i \hat k} \sigma^-). \end{equation}\]This gives us a Brillouin zone as well with $k\in[-\pi,\pi)$. Here we write the $k$-space Hamiltonian out in three ways for pedagogical reasons

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} H_k & = - (t_1 + t_2 \cos k) \sigma_x - t_2 \sin k \sigma_y, \\ H_k & = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & -t_1 - t_2 e^{-i k} \\ -t_1 - t_2 e^{ik} & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \end{aligned} \label{eq:ssh-kspace} \end{equation}\]and finally the general form

\[\begin{equation} H_k = \epsilon_0(k) - \mathbf d(k) \cdot \sigma, \label{eq:general-k-space-two-band} \end{equation}\]where for our model $\epsilon_0(k) = 0$, $d_x(k) = t_1 + t_2 \cos k$, $d_y(k) = t_2 \sin k$, and $d_z(k) = 0$. If we write $\mathbf d(k) = d(k) ( \cos \phi_k \sin \theta_k, \sin \phi_k \sin \theta_k, \cos \theta_k)$, then the general solution to this two-level problem is

\[\begin{align} \epsilon_\pm(k) & = \epsilon_0(k) \pm d(k), \end{align}\]with solution for the lowest band ($\epsilon_-(k)$)

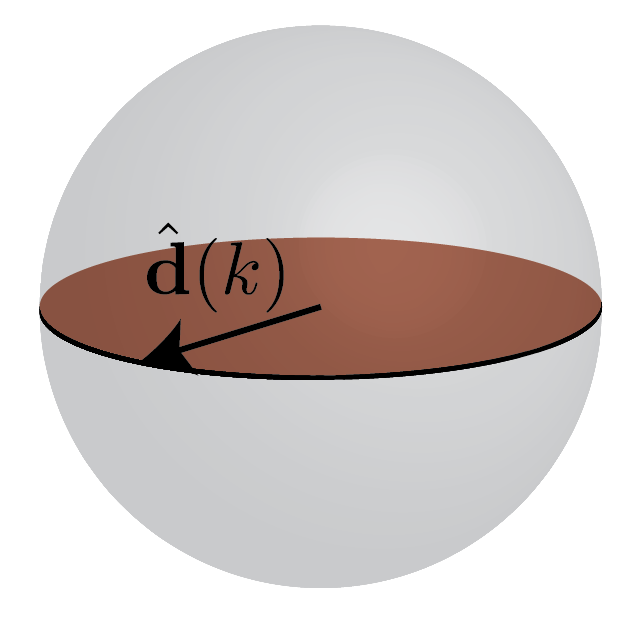

\[\begin{equation} \lvert{u_k}\rangle = \begin{pmatrix} \cos(\theta_k/2) \\ \sin(\theta_k/2) e^{i\phi_k} \end{pmatrix}. \label{eq:uk_north} \end{equation}\]The nice thing about these $\lvert u_k \rangle$ is they are easily represented by points on the Bloch sphere. For our model \eqref{eq:ssh-kspace}, we have $\theta_k = \pi/2$, and $e^{i\phi_k} = (t_1 + t_2 e^{-i k})/|t_1 + t_2 e^{-ik}|$. Note that only the unit vector

\[\hat{\mathbf d}(k) = \frac{\mathbf d(k)}{d(k)}\]controls the wave function (and as we’ll see, the topology). Lastly, the energy bands look like

Berry connection, Berry phase, and polarization

For the necessary mathematical machinery, we refer to Ch. 3 of

We can compute the Berry phase for this band which is exactly related to the polarization (see Ch. 4 of

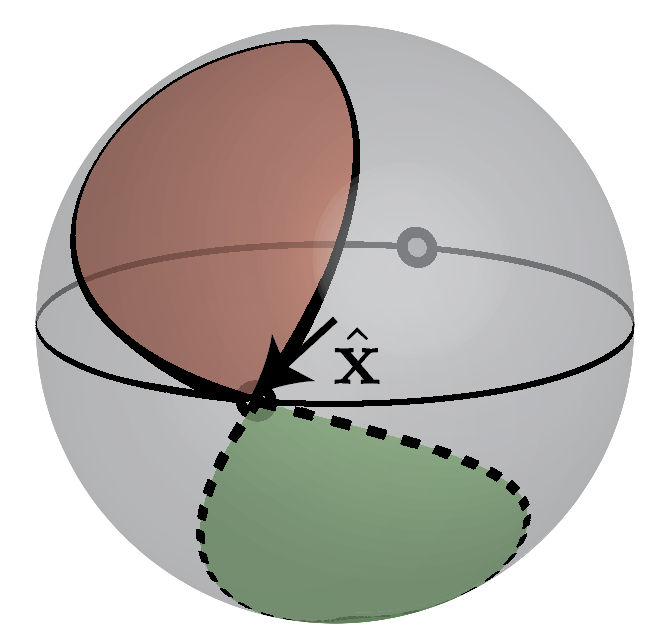

It is tempting to change variables in the integral to $\oint d \phi_k$, but we need to understand what the closed curve $\oint$ represents. Since $d_z=0$ we can think purely in terms of the equator of the Bloch sphere and either $\phi_k$ makes it around the sphere or it does not as indicated in Fig. 3 below.

From this information, we can read off what the results from the Berry phase calculation for polarization becomes

\[\begin{equation} P = \begin{cases} -e/2 & t_1 < t_2, \\ 0 & t_1 > t_2. \end{cases} \quad \mathrm{mod}\, e \end{equation}\]The first case $t_1 < t_2$ is represented in red in Fig. 3 and we call it “topological” while the case $t_1 > t_2$ we call “trivial”.

One might wonder at this point why these two phases are distinguishable at all since Fig. 1 shows two configurations that when rotated about an $A$ site appear to be exchanged. The answer to this comes from two sources (1) domain walls between configurations (to be explored in a future post) and (2) edges. Fig. 1 shows the situation with edges: either the lattice ends with a strong bond or a weak bond. Both of these situations come into full focus when we consider edge states resulting from the topology.

Symmetries

Aside from translation symmetry, which we have already used to find $H_k$, what other symmetries are in the problem? In particular, what discrete symmetries can we identify? The model as written down in \eqref{eq:ssh-kspace} has the following symmetries:

- Time reversal symmetry

- Chiral symmetry

- Particle-hole symmetry

- Inversion symmetry

Each of these is important for the topology of the problem.

Time-reversal symmetry

The first symmetry we identify is the anti-unitary symmetry of time-reversal. In this model it takes the form $T = K$ where $K$ is complex conjugation (in the real space basis). In terms of our $k$-space Hamiltonian we have

\[T H_k T^{-1} = H_{-k}.\]For a the general two-band Hamiltonian \eqref{eq:general-k-space-two-band}, we have

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \epsilon_0(k) & = \epsilon_0(k), & d_x(k) = d_x(-k), \\ d_y(k) & = -d_y(-k), & d_z(k) = d_z(-k). \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]In general, this does not constrain our problem enough to give us topology since if we imagine taking $k$ and mapping it onto the sphere (some closed path) given the above constraints, at $k=0$ and $k=\pi$ $\mathbf d$ is constrained to be in the $xz$-plane. Under these constraints, any path can be continuously deformed onto just a single $\mathbf d(k) \equiv \mathbf d_0$, indicating a trivial topology.

We clearly need something to limit our available paths.

Chiral Symmetry

Chiral symmetry is an odd symmetry. It is unitary, however the symmetry relates the positive and negative energies. In particular, the chiral operator $\sigma_z$ anti-commutes with the Hamiltonian $\{H, \sigma_z\} = 0$ or in terms of its action on $H_k$

\[\sigma_z H_k \sigma_z = - H_k\]We can directly discern from this that for every positive energy states we can construct a negative state $\sigma_z \lvert E_k \rangle = \lvert - E_k \rangle$. For the two-level problem we are working with, the core issue constraint is

\[\begin{align} \epsilon_0(k) & = 0 & d_z(k) & = 0. \end{align}\]This constrains us to be on the equator (see Fig. 4)

The winding number can be defined safely with the gauge chosen in \eqref{eq:uk_north}, this is the polarization but now with $\mod e$, so to differentiate it we call it

\[\begin{equation} \nu_{\mathbb Z} = \frac1{\pi} \oint_{BZ} A(k) = -\frac{1}{2\pi} \oint_{BZ} dk \, \frac{d\phi_k}{dk}. \end{equation}\]However, we would like a gauge-independent quantity and if we let $\lvert u_k \rangle \rightarrow e^{i\alpha_k} \lvert u_k \rangle$ then we can change the above expression by an even integer. To remedy this, we first note that general solutions now take the form

\[\begin{equation} \lvert u_k \rangle =e^{i\alpha_k} \frac1{\sqrt2} \begin{pmatrix}1 \\ e^{i\phi_k} \end{pmatrix} \end{equation}\]And we can in fact obtain the phase difference $\phi_k$ by a slight modification of the Berry connection to include the chiral operator

\[\begin{equation} \nu_{\mathbb Z} = -\frac1{\pi} \oint_{BZ} dk \langle u_k | \sigma_z | i\partial_k u_k \rangle = -\frac1{2\pi} \oint_{BZ} dk\, \frac{d\phi_k}{dk}. \end{equation}\]Thus chiral symmetry gives us a strong constraint which leads to an integer topological number $\mathbb Z$.

This winding number can also be computed directly from the Hamiltonian. Two natural ways of getting it include use of the $\mathbf d(k)$ vector

\[\begin{equation} \nu_{\mathbb Z} = \frac{1}{2\pi} \oint_{BZ} \left(\hat{\mathbf d}(k) \times \frac{d}{dk}\hat{\mathbf d}(k) \right) \cdot \hat{\mathbf z} \, dk, \end{equation}\]and the second, which generalizes to multiple bands requires us put our Hamiltonian in the form

\[\begin{equation} H_k = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & h(k) \\ h^\dagger(k) & 0 \end{pmatrix}, \end{equation}\]and for the matrix $h(k)$ we have

\[\begin{equation} \nu_{\mathbb Z} = \frac1{2\pi} \oint_{BZ} dk \frac{d}{dk} \log \det h(k). \end{equation}\]Physically, this symmetry relies on there not being a term proportional to $\mathbb{I}$ or $\sigma_z$ in the Hamiltonian which in terms of sublattices means that no potential is allowed and we are only allowed hoppings from the $A$ sublattice to the $B$ sublattice. In polyacetyline this is not an actual symmetry since no physical process prevents hopping from within a sublattice. We therefore need to argue for some other symmetry in the problem that leads to topology.

Inversion symmetry

The inversion symmetry in the SSH model (equivalently, reflection symmetry or 180-degree rotation symmetry) is best understood by taking Fig. 1 and flattening it out as in Fig. 5 below

This is a traditional unitary symmetry of the problem and its action on the $k$-space Hamiltonian is to relate $k$ to $-k$ and to exchange the $A$ sublattice with the $B$ (this is accomplished with $\sigma_x$)

\[\sigma_x H_k \sigma_x = H_{-k}.\]In terms of the two-band system

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \epsilon_0(k) & = \epsilon_0(-k), & d_x(k) & = d_x(-k), \\ d_y(k) & = - d_y(-k), & d_z(k) & = - d_z(-k). \end{aligned} \label{eq:inversion_twobands} \end{equation}\]Our first hint of two topologically distinct classes comes from there being two inversion symmetric polarizations possible $P = 0 \mod e$ or $P = e/2 \mod e$ since in both cases $P = -P \mod e$ (polarization changes signs under inversion).

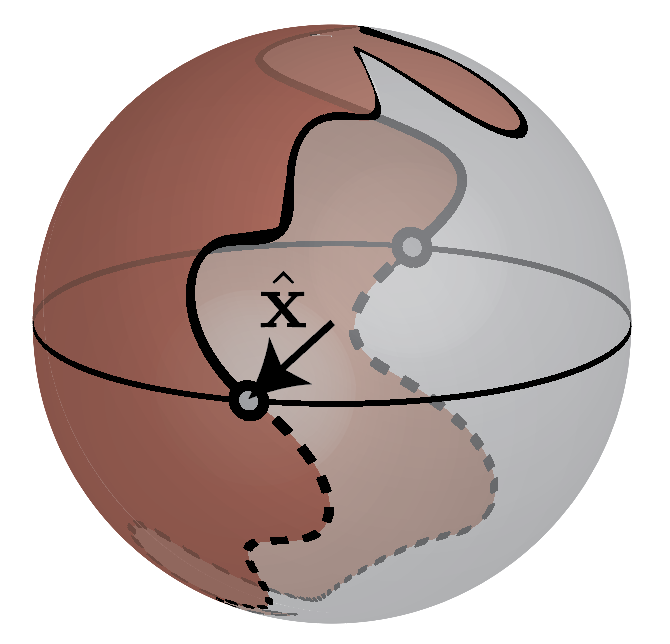

Now the unit vector $\hat{\mathbf d}: S^1 \rightarrow S^2$ maps a closed path onto the (Bloch) sphere. If we permit any continous change in $\hat{\mathbf d}$ every closed path can be reduced to a single point (this is why without symmetries in 1D the topology is trivial). With the added constraint of inversion though, we have two special points $\mathbf d(0) = d_x(0) \hat{\mathbf x}$ and $\mathbf d(\pi) = d_x(\pi) \hat{\mathbf x}$ and the path $k\in[0,\pi]$ completely determines the path $k\in[-\pi,0)$. This leads to two classes of paths, one in which $\mathrm{sgn}(d_x(0)d_x(\pi)) > 0$ and the other in which $\mathrm{sgn}(d_x(0)d_x(\pi)) < 0$, and continuously changing $\hat{\mathbf d}$ while respecting inversion symmetry cannot take one class of paths to the next. These two types of paths are represented below in Fig. 6.

This suggests a simple way to differentiate topological and trivial phases known as symmetry indicators. If we look at the inversion symmetric points, the Hamiltonian has the form

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} H_{k=0} & = \epsilon_0(k=0) - \sigma_x d_x(k = 0) & H_{k=\pi} & = \epsilon_0(k=\pi) - \sigma_x d_x(k=\pi). \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]The inversion operator at these points is simply $\sigma_x$ with $\lvert{u_{k=0}}\rangle$ and $\lvert{u_{k=\pi}}\rangle$ both eigenvectors of that operator with eigenvalues $\xi_{0} = \mathrm{sgn}(d_x(k=0))$ and $\xi_\pi = \mathrm{sgn}(d_x(k=0))$, respectively. There is then a $\mathbb Z_2$ index which we can define simply by

\[\begin{equation} \tilde \nu_{\mathbb Z_2} = \xi_0 \xi_\pi = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{trivial,} \\ -1, & \text{topological.} \end{cases}. \end{equation}\](we have defined $\tilde \nu_{\mathbb Z_2} = (-1)^{\nu_{\mathbb Z_2}}$.) The $\mathbb Z_2$ invariant is also computed, as we have suggested, by the polarization

\[\begin{equation} \nu_{\mathbb Z_2} = \frac1{\pi} \oint_{BZ} dk \, \langle u_k | i \partial_k u_k \rangle \mod 2, \end{equation}\]such that $P = \frac{e}{2}\nu_{\mathbb Z_2}$.

By just looking at two points in the Brillouin zone, we can discern if the phase is topologically nontrivial. In summary, inversion symmetry alone gives us $\mathbb Z_2$ topology.

Particle-hole symmetry

The last symmetry we consider is actually a combination of previous symmetries, particle-hole symmetry for this problem will be the anti-unitary symmetry made by combining time-reversal symmetry and chiral symmetry. In fact, for this problem

\[C = \sigma_z T = \sigma_z K,\]It acts on our $k$-space Hamiltonian such that

\[C H_k C^{-1} = - H_{-k}.\]In terms of the two-band model we have the constraints

\[\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \epsilon_0(k) & = - \epsilon_0(-k) & d_x(k) & = d_x(-k), \\ d_y(k) & = -d_y(-k) & d_z(k) & = - d_z(-k). \end{aligned} \end{equation}\]These constraints are suprisingly close to the constraints place upon us due to inversion symmetry \eqref{eq:inversion_twobands} except for $\epsilon_0(k)$ which here must be odd in $k$ instead of even in $k$. However, that detail does not affect the wavefunctions which only follow $\mathbf d(k)$ and so by very similar logic to inversion symmetry if we have this particle-hole symmetry, we have a $\mathbb Z_2$ topology.

Cartan Classification

Each individual Hamiltonian such as \eqref{eq:ssh-kspace} has their own particular symmetries. However, to speak of topology one must think closely about what terms could be added to the Hamiltonian. This is seen very clearly in the SSH model where we have enumerated many symmetries, but have argued that some of them (such as the chiral symmetry) do not make sense for the physical symmetry. Nonetheless, it is a useful exercise to take each symmetry seriously and build out what topology it implies. For the two-band systems suggested by the SSH model \eqref{eq:general-k-space-two-band} we have done just that, and the result matches what is known from topological classification

| T | C | S | Topology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | $\mathbb Z_2$ |

| 0 | 0 | 1 | $\mathbb Z$ |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | $\mathbb Z$ |

T represents time reversal, C represents particle-hole symmetry, and S represents chiral symmetry (0 is no symmetry, 1 is that it is present).

Additionally, we can include inversion symmetry. The only relevant combination is time-reversal and inversion, which leads directly to $d_z(k) = 0$ and allows us to use the arguments for chiral symmetry to obtain a $\mathbb Z$ invariant (though with a finite $\epsilon_0(k)$ which needs to be considered only for purposes of having a direct gap between bands as well as when taking into account Fermi energies)

| T | Inversion | Topology |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | $\mathbb Z_2$ |

| 1 | 1 | $\mathbb Z$ |

All of this applies to the entire lower band of this system, when we are in the insulating state. Partially filled bands don’t allow us to perform many of the full integrals over the whole Brillouin zone and therefore cannot be classified as we have mentioned.

Conclusions

This post has been mainly concerned with the bulk classification of the topology inherent in the SSH model, carefully going through each symmetry and its relation to the topological classification (as well the corresponding topological numbers). In this system, the main observable for the model are edge states, which we have not discussed here.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: